In the aftermath of Hurricanes Florence and Michael, farmers across the Southeast face devastating losses to this year’s harvest and livestock operations. Through the Farm Bill and other authorizing statutes, Congress has created several programs that allow farmers to receive financial assistance after a natural disaster. These USDA programs go far in helping affected individuals recover and move forward. However, USDA disaster relief programs do not acknowledge that climate change will likely increase the frequency and cost of future natural disasters.

The previous post in this series explored the variety of relief programs available to assist farmers after a natural disaster. While disaster relief programs are available, the programs fails to adequately account for climate change. This post will explain that linking climate change and disaster relief is important to protect future harvests, ensure fiscal stability for farmers, and reduce the need for Congress to pass ad hoc disaster appropriations.

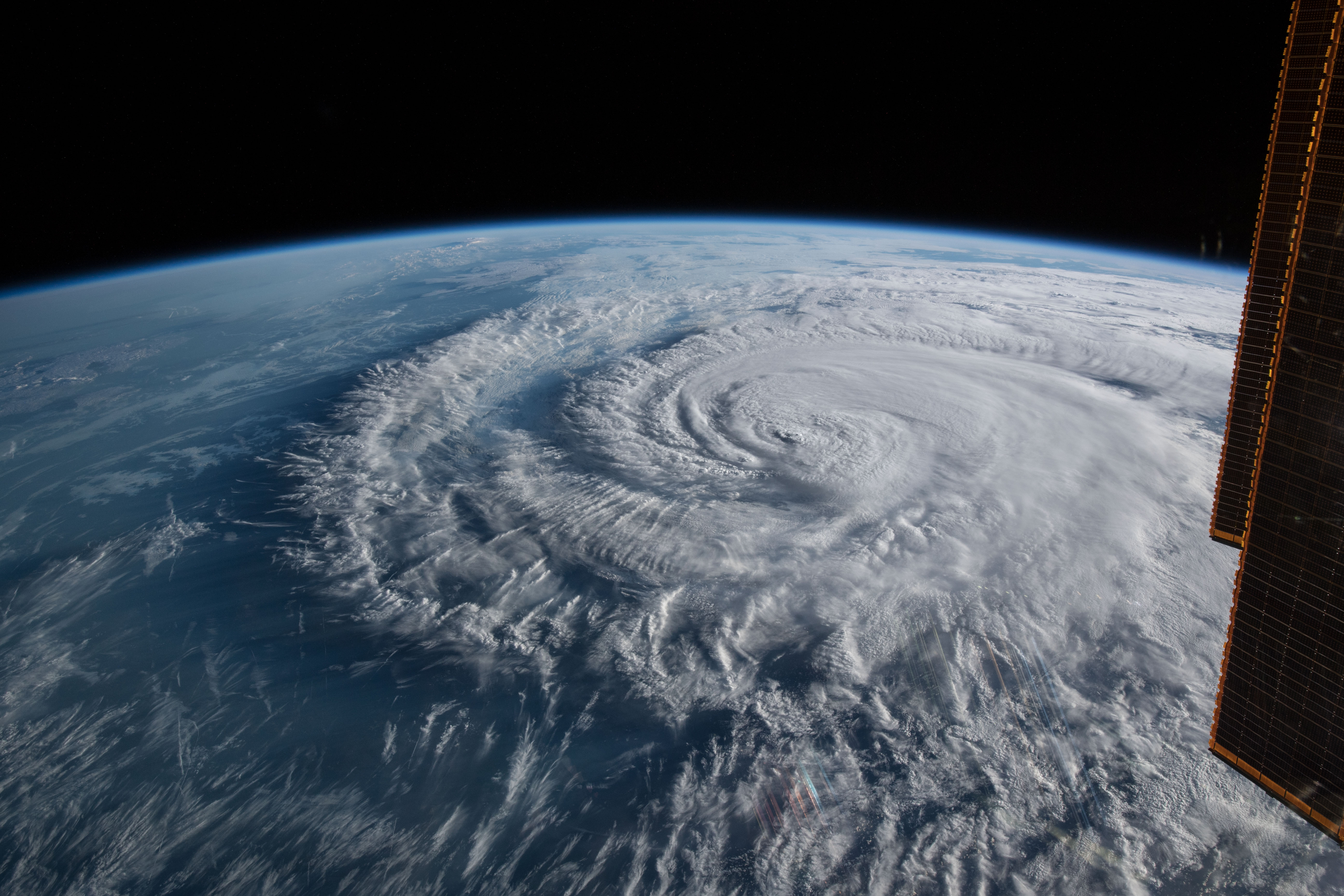

In recent years, a spate of climate-change-enhanced natural disasters have ravaged the agricultural community. For example, Hurricane Florence’s punishing rains water-logged North Carolina. The North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services estimated the total agricultural losses in the state to be around $1.1 billion. This comes on the heels of a $400 million loss from Hurricane Matthew in 2016. In Florence, livestock were decimated, with 4.1 million poultry and 5,500 hogs perishing in the storm. Moreover, North Carolina usually accounts for more than half of the nation’s sweet potato crop, but this year’s sweet potato harvest is in doubt after water inundated the fields. In addition to soaking and spoiling crops, the immense amount of rain caused structural damage to hog waste lagoons, costing money and threatening surrounding communities with toxic water pollutants. Research has already found that Florence was up to 50 percent wetter than it would have been in the absence of climate change. Climate change will continue to affect the severity and frequency of disasters like Hurricane Florence.

Even with permanently-authorized USDA programs in place, Congress has needed to pass ad hoc disaster relief appropriations in order to provide adequate support to farmers after disasters like Florence and Matthew. For example, the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 appropriated additional funds to help cover crop and livestock losses due to hurricanes and wildfires in 2017. Even more recently, the Chairman and Ranking Member of the House Appropriations Committee’s Subcommittee on Agriculture are pushing for another disaster relief bill to respond to the 2018 hurricane and wildfire seasons. If American farms remain ill-prepared for increasingly intense storms, disaster costs will continue to rise. Because of these costs, Congress and USDA should connect disaster relief funding with suggestions for how farmers can make their farms more resilient to the impacts of climate change.

To be sure, USDA has not ignored climate change. The Reference Guide mentioned in the previous post lists disaster resources including USDA “climate hubs,” which are meant to help farmers make “management decisions” in light of “increasing drought.” Other resources listed in the Guide focus on sustainable development and conservation. Programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program provide farmers with needed tools to create sustainable maintenance plans for their land and water and to prepare for uncertain weather.

That being said, USDA’s climate resilience programs operate separately from the disaster relief programs. As one example, the climate and conservation programs on the Reference Guide are listed under the heading of “technical assistance,” a separate category from the “disaster payments for agricultural losses” section. While such a distinction might seem trivial, in fact, USDA disaster relief money is not directed toward making farms more able to withstand natural threats. Some disaster money requires recipient farmers to purchase future risk coverage, but farmers are under no obligation to adapt their operations in ways that would lessen the impact of future disasters. Many may choose to do so on their own, but not all will. USDA can increase the number of farmers taking climate adaptation action by making climate adaptation part and parcel of providing disaster relief. When distributing relief money, USDA should make suggestions for how the farm could adapt and support farmers as they make those changes. Those changes can make farms more resilient and future disaster spending less necessary.

USDA has a strong cohort of relief programs that help farmers recover from natural disasters. USDA has also acknowledged that farmers can take steps to reduce the impact that climate change will have on the farm’s operations. In order to make disaster relief programs even more effective, USDA should include climate adaptation guidelines and technical assistance when distributing money so that farmers can build sustainable operations and can count on adequate disaster relief funding to be available in the future. While continuing to provide immediate and much-needed assistance to farmers after a disaster, that assistance can and should also help farmers prepare for the future.