Recently, USDA has taken a particular interest in mental health concerns in rural America. This two part blog post will address what USDA is doing to address both the opioid crisis and farmer suicide.

Farmer Suicide

In 2016, the CDC reported that among various occupational groups, suicide rates were highest in the farming, fishing, and forestry (Triple-F) industry at 84.5 suicides per 100,000 people. This study was widely cited by various news outlets, but on June 29, 2018, the CDC published a notice that some “results and conclusions” of the study “might be inaccurate as a result of coding errors for certain occupational groups.” In an email to The New Food Economy, a CDC spokesperson clarified the mistake: farmers and ranchers had been classified as falling under the Triple-F category by the authors of the CDC study, but the Department of Labor classifies farmers and ranchers as managers. The “farming” component of the Triple-F category actually refers to agricultural workers, not farmers. Because of this, the Triple-F suicide rate was inflated, while the Management suicide rate was underreported. It is important to note the demographic differences between farmers and agricultural workers: farmers are overwhelmingly white and have household incomes around $79,000 per year, while agricultural workers are 80% Hispanic and have household incomes of approximately $23,000 per year.

Despite the current uncertainty surrounding the numerical data, farmer and farm-worker suicide clearly continue to be a public health concern. The CDC’s email to the New Food Economy said that after data revisions, the Triple-F category has the third-highest suicide rate among occupational groups. Furthermore, farmworkers also experience high rates of other mental health conditions, such as anxiety and alcoholism.

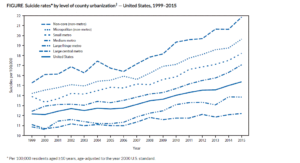

Photo: CDC (Showing higher rates of suicide in rural counties, though not farmer exclusive)

In April of this year, Senator Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) sponsored the “Facilitating Accessible Resources for Mental health and Encouraging Rural Solutions for Immediate Response to Stressful Times Act”—known as the FARMERS FIRST Act. This Bill is a “marker bill”—not intended to be passed into law on its own, but rather a way for legislators to roll out parts of their agendas before an omnibus piece of legislation like the Farm Bill. The FARMERS FIRST Act matched the Senate proposed amendments to the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network (FRASN), discussed below, and would also establish comparable state-level networks funded by competitive grants. But agricultural workers were not included in FARMERS FIRST, and the final Senate version of the Farm Bill does include these workers.

The 2008 Farm Bill first created FRSAN, but the network was never funded. The current Senate version of the Farm Bill would authorize the appropriation of $10 million per fiscal year from 2019 through 2023. The Senate version also requires the Secretary of Agriculture to develop a report on the state of mental health among farmers and ranchers. The House Bill would re-authorize FRSAN, but would not significantly alter it or introduce a funding amount.

The Farm Bill is currently expired, and it is hard to predict whether it will be reauthorized during the current lame duck Congressional session or after new legislators are sworn in next year. We will have to wait and see whether the Farm and Ranch Stress Assistance Network will be amended in keeping with the vision behind the FARMERS FIRST Act.

What’s Next

The rural opioid crisis and the high rates of farmer and farmworker suicide can both be viewed as symptoms of a larger problem impacting rural America: lack of access and connectivity to various services, paired with economic depression and an uncertain future. But it does not seem that USDA has considered a cross-cutting solution with the goal of addressing both at the same time. Perhaps there is an opportunity for programs such as the Community Facilities Grant and the Distance Learning and Telemedicine Grant Programs to solicit and fund innovative mental health solutions as a whole, from opioid addiction to depression and suicidal ideation. Or perhaps FRSAN can be expanded—and funded—to explicitly incorporate drug abuse and addiction counseling. With interconnected health concerns, all symptomatic of larger problems of rural development and prosperity, we should consider the potential for an interconnected approach to solutions.