Recently, USDA has taken a particular interest in mental health concerns in rural America. This two part blog post will address what USDA is doing to address both the opioid crisis and farmer suicide.

The Opioid Crisis

The entire country has been hard-hit by the opioid crisis, but rural communities are especially impacted. Drug overdose deaths in rural communities have surpassed those in urban communities. An estimated 74% of farmers and farmworkers have been directly impacted by the opioid crisis, according to a study sponsored by the American Farm Bureau Federation and the National Farmers Union, meaning that they or someone close to them has used illicit opioids or is suffering from addiction. Rural areas do not always have the capacity to address the problem at its current scale. South Dakota and Arkansas, for example, have an opioid treatment need-to-capacity ratio of about 7:1.

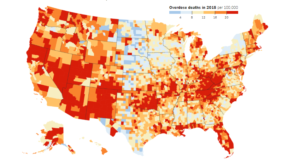

Photo: NY Times (showing clusters of overdose deaths in rural areas)

There are several factors that contribute to the rural opioid crisis. Rural communities tend to have older populations, who suffer more from chronic medical conditions that might result in legal painkiller prescriptions. These prescriptions can act as a gateway to addiction. Individuals in rural communities also tend to hold physically risky jobs, and the resulting injuries can also lead to legal prescriptions that develop into addiction. Because of geographic isolation, alternatives to prescription drugs—such as physical therapy—are often unavailable. Rural areas are currently facing high rates of poverty, unemployment, substandard housing, and regional economic depression. Finally, the geographic isolation of rural communities means that residents often do not have access to mental health professionals or treatment facilities once an addiction has developed.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) sees its role in this public health crisis as twofold: immediate and direct response through prevention, treatment, and recovery services; and addressing deeper systemic issues such as a lack of medical services and connectivity. To these ends, USDA offers two grant programs: the Community Facilities Grant Program and the Distance Learning and Telemedicine Grant Program (DLT).

The Community Facilities Grant was a pre-existing program that recently set aside $5 million to fund projects aimed at addressing the opioid crisis. Eligible projects are those that provide physical facilities, such as buildings, vehicles, or other equipment, and offer an innovative component, such as a unique collaboration between different organizations or levels of government. The targeted community must have a population below 20,000 to qualify as “rural.”

The DLT Grant Program has been in place since the 1990s and similarly has now earmarked $20 million for projects that specifically address the opioid crisis. DLT defines “telemedicine” as “a synchronous telecommunication link to an end user from medical professionals at separate sites in order to exchange health care information for the purpose of providing improved health care services to residents of rural areas;” this allows a medical “hub” to provide interactive and individualized health services to various rural “spokes.” Grants may be used to purchase necessary equipment, construct broadband capacities, or provide technical assistance or instructional programming.

On October 5, 2018, USDA introduced the Community Assessment Tool, an interactive data tool that helps to determine causes and impacts of opioid abuse within any particular community. This tool displays as a map of the United States broken down by counties within states; the counties are colored to reflect the number of opioid deaths per 100,000. The map then offers various socioeconomic overlays, including race and ethnicity, poverty and unemployment rates, disability status, and educational attainment. And on October 30, USDA introduced its Rural Resource Guide to Help Communities Address Substance Use Disorder and Opioid Misuse, which consolidates hundreds of federal resources.

These resources are targeted at various topics, from the justice system to transportation needs, and diverse populations, from Native Americans to the elderly to parents. Many resources provide funding, but some provide other resources, such as data, technical assistance, or direct services. These two resources—the Community Assessment Tool and the Rural Resource Guide—are designed to help communities determine both the specific context in which they are combating opioid addiction and the resources available to them in addressing it.

What’s Next?

The rural opioid crisis and the high rates of farmer and farmworker suicide can both be viewed as symptoms of a larger problem impacting rural America: lack of access and connectivity to various services, paired with economic depression and an uncertain future. But it does not seem that USDA has considered a cross-cutting solution with the goal of addressing both at the same time. Perhaps there is an opportunity for programs such as the Community Facilities Grant and the Distance Learning and Telemedicine Grant Programs to solicit and fund innovative mental health solutions as a whole, from opioid addiction to depression and suicidal ideation. Or perhaps FRSAN can be expanded—and funded—to explicitly incorporate drug abuse and addiction counseling. With interconnected health concerns, all symptomatic of larger problems of rural development and prosperity, we should consider the potential for an interconnected approach to solutions.