Stephanie Kelemen is a law student enrolled in the Harvard Law School Food Law & Policy Clinic and guest contributor on this blog.

Buried deep in the 2018 Farm Bill, under the Conservation title, Congress established a peculiar program with $75m of mandatory funding: the Feral Swine Eradication and Control Pilot Program. Prior to encountering this Section, I had never even heard of feral swine. The provision states that the program is necessary “to respond to the threat feral swine pose to agriculture, native ecosystems, and human and animal health,” but if many people have never heard of feral swine, how big could this problem really be?

Really big, apparently. Those familiar with the issue refer to it as a “feral swine bomb” due to the rapid rate with which these animals, originating from agricultural pigs bred to have large litters, are reproducing. But it is not the mere prevalence of feral swine that is the problem, but rather the destruction they cause. Feral swine attack livestock, destroy native plants, and mow down crops, resulting in an estimated $2.5 million in damage in the U.S., a figure which grows with the population size.

Given the high intelligence of feral swine, amateur hunters have in some cases exacerbated the problem as these pigs expand their roaming range and become nocturnal after being shot at. The USDA has a list of techniques for “management” of what it deems an invasive species by local authorities or skilled hunters. Though it designates “lethal techniques” as more effective, there is no mention of productive uses for these animals. This surprised me considering the U.S. slaughters over 120 million pigs for consumption each year. If feral swine are as “delicious” as some claim, then why aren’t they being sent to our supermarkets? To get to the bottom of the issue, I decided to purchase, cook, and eat some feral swine myself.

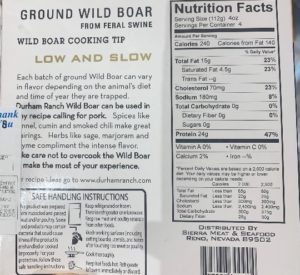

After calling several local butchers with no luck, I found one that offered a variety of feral swine products. I expected to find various cuts of meat in shrink wrap (bottom shelf in image below), but to my surprise there was also a packaged offering alongside other types of exotic meat with images showing the cooked product.

In the culinary context, feral swine is referred to as “wild boar,” giving it a more exotic and less suspicious sounding name (though all products are required to include “feral swine” somewhere on the label). This label included a particularly appealing description, and at $17 per pound, seemed to be marketing itself as a delicacy.

Having purchased the meat, I found a recipe to make a ragu to be served over pasta. Consistent with the label’s recommendation, the recipe I used required several hours of simmering over a low burner.

The product was a yummy meat sauce that tasted like regular pork with a nutty flavor. Was it a delicacy? At least not with my cooking, but it was certainly more than just edible.

From this experience, I can share three findings:

- Feral swine is currently too expensive to see a meaningful increase in consumption. In my experience, feral swine does not taste different enough from standard pork to justify paying nearly twice the price. Putting taste aside, many people may be hesitant to try an unfamiliar meat with such a large price difference.

- If feral pigs must be killed, they should be slaughtered for consumption. Unlike swine raised in industrial operations, feral pigs are inherently free-range and fed on natural diets, giving them a clean taste. Because the same food-safety standards apply to both types of meat, feral hogs must be brought to the slaughterhouse live and inspected by the USDA, making them equally safe for consumption. Finally, since feral swine already exist in the wild, they are an effectively carbon-neutral and more humane meat product. Killing feral swine in the wild rather than trapping and bringing them to a slaughterhouse should be viewed as a form of food waste.

- The next Farm Bill should incentivize a less wasteful feral swine control program. Whether it is providing more resources for live-trapping or subsidizing feral swine products, the next farm bill can work toward a strategy that prioritizes productive use of meat rather than merely rapid extermination.

The views and opinions expressed on the FBLE Blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of FBLE. While we review posts for accuracy, we cannot guarantee the reliability and completeness of any legal analysis presented; posts on this Blog do not constitute legal advice. If you discover an error, please reach out to contact@farmbilllaw.org.